Methodology

Our values

Before making precise proposals, the ethical framework and the values of science have to be underlined. In the 20th century, the CUDOS norms were characteristics of the science ethos according to Merton (Merton, 1942, 1973): Communalism, Universalism, Disinterestedness, Organised Scepticism. However, this system that isolated the scientific community from the rest of the society does not correspond anymore with the more inclusive science and society landscape. The scientific integrity principles and responsibilities, as set out for example in the Singapore Statement on Research Integrity (2010), the UNESCO Recommendations on Science and Open Science (2017), the Hong Kong principles (Moher, 2020), the European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity (ALLEA, 2023), and the CARE principles (Carroll et al., 2020) constitute representative international efforts to encourage the development of unified policies with the long-range goal of fostering greater integrity, inclusivity, respect for indigenous rights and further unified policies. As these general rules address facets of the research practices and tend to be taken into account both in education and in research assessment criteria, they constitute a general framework for all recommendations below.

Identifying the needs and research focus areas

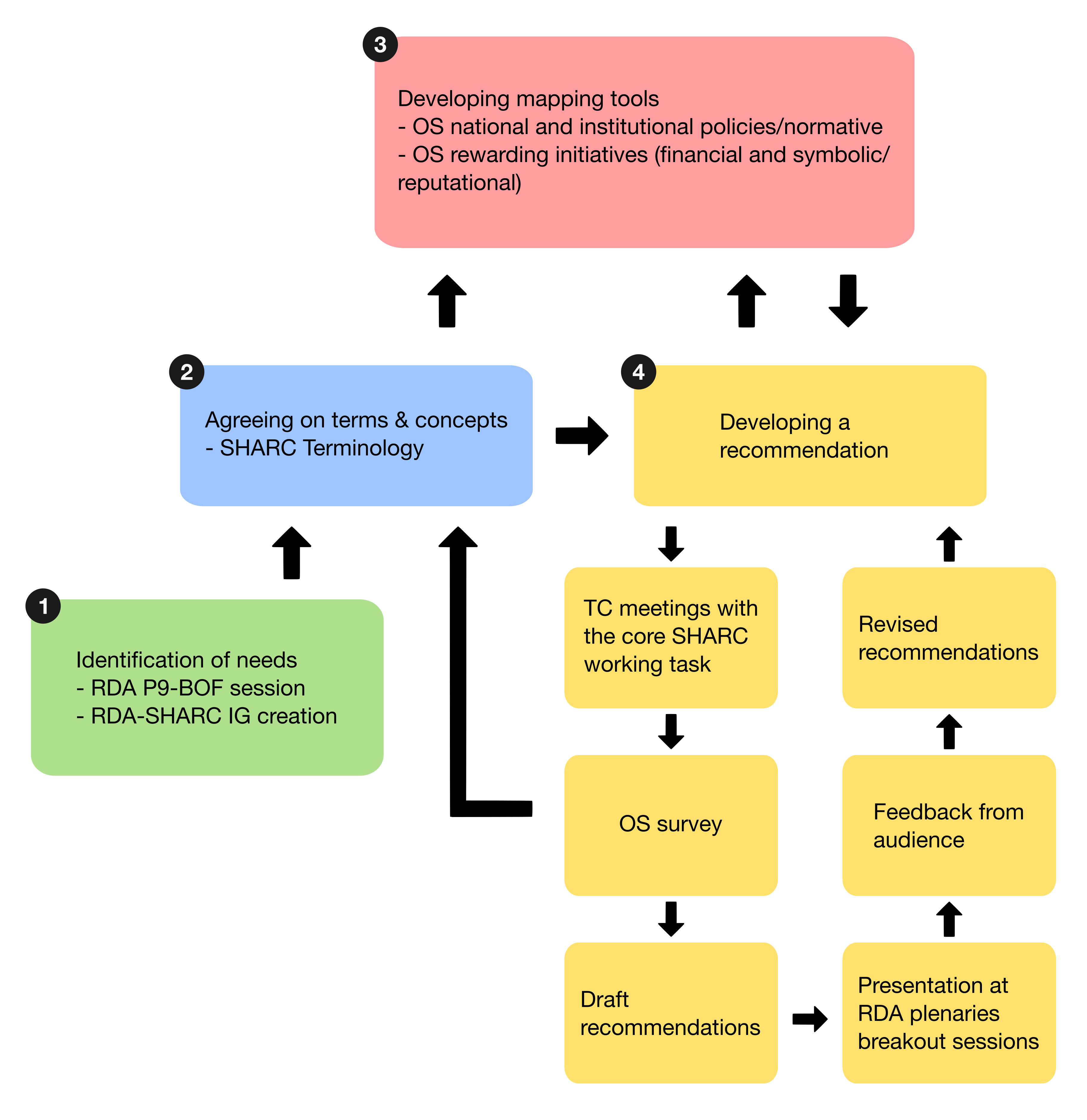

The first step of our work was a Birds of a Feather (BoF) session held during Research Data Alliance Plenary 9 (Figure 1, step 1). The session focused on the hurdles involved in opening up data and other research outputs in the research process, as well as on rewarding schemes and the extent of their use or absence regarding sharing data and other outputs. The discussions spurred i) the creation of the RDA-SHARC interest group that first focused on the design of a human readable FAIR assessment tool (David et al., 2024) and ii) the establishment of a core evolving sub-working group gathering active members developing guidance and recommendations.

As part of this core group (namely, the authors of the present work), we further refined the needs related to recognition throughout i) additional interactive working sessions at RDA plenaries 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 17, 19 and 20, ii) regular teleconference meetings, emails and asynchronous exchanges (e.g., via Google Doc).

Agreeing on terms and concepts: terminology

The preparatory step led us to develop a terminology with regards to rewarding in science as a common understanding of the terms and concepts mapping this landscape (Figure 1, step 2). We identified all related terms we could think of as to research recognition schemes and categorised them as different types of possible rewards and reward mechanisms (see our Terminology).

From the literature, we agreed that types of rewarding can range from intangible reputational rewards such as recognising the contribution made by collaborators through acknowledgments and citations and co-authorship (Hicks, 2012; Latour & Woolgar, 1979) and other tangible rewards (e.g., funds, prizes, career advancement, hiring, and patents) (Haeussler, Jiang, Thursby, & Thursby, 2014; Nelson, 2016; Shibayama & Lawson, 2021). Opportunities for future collaboration were also reported as possible rewards for sharing (Haeussler et al., 2014; Shibayama & Lawson, 2021).

Developing mapping tools

To further facilitate the use of our recommendations, as a third step (Figure 1) we built several mapping tools that compiled existing policies and rewards related-tools:

OS Policies, gathers brief descriptions and links to the main OS policies across many countries, pointing to rewards related information whenever specified;

Rewarding tools (OS Awards/Prizes, OS Funds, OS Badges/Certificates/Tokens, OS Champions), display examples of existing rewarding tools that were brought to our attention along the various discussions conveyed within SHARC’s meetings, RDA plenaries and as a result of the SHARC OS survey (described in the next section).

Finalising recommendations

The fourth step focused on developing actionable recommendations based on the gaps identified during the SHARC IG working sessions and meetings (Figure 1, step 4). These recommendations aimed to i) guide researchers and scientists in the existing rewarding landscape as to how to get some credit in practice, and ii) raise awareness among a number of actors who are part of the research assessment system on which rewarding mechanisms (so far missing) to provide and implement to make the whole system work.

To that aim, a survey was first designed to identify perceptions and expectations of various research communities regarding how OS activities are taken into consideration and rewarded; this survey was sent out to the RDA community at large and various other networks related to members of our core group. Details of the survey methodology and results are available in Grattarola et al. (2024). We then developed the set of recommendations as a multiple-step process based on the results of the survey with back-and-forth exchanges between members of the RDA-SHARC core group and participants in the RDA-SHARC sessions.

Which actions to implement first will depend on the stage each stakeholder is at. Therefore, we intentionally did not prioritise the actions in our recommendations.